|

HOME |

ABOUT | INDEX |

NEWS |

FACEBOOK |

CONTACT

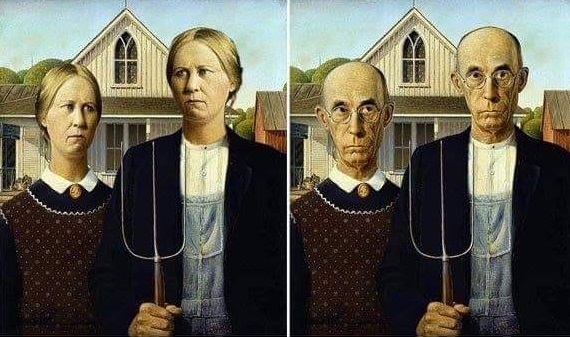

RURAL

Appalachian | Small Town | Country | South

Small

Town LGBTQ Pride

What

does LGBTQ pride look like in places

like South Carolina or Georgia? How does

it feel to be gay in Mississippi or

Louisiana? What is life like for an

LGBTQ person in Alabama or Tennessee?

How is LGBTQ pride different in Texas or

Florida?

You should attend a

rural gay pride

event this

year. Why? Because,

you just might learn

a little something

about LGBTQ country

folks. You probably

do not realize that

LGBTQ people

actually live in

small towns. You

very likely do not

know that there are

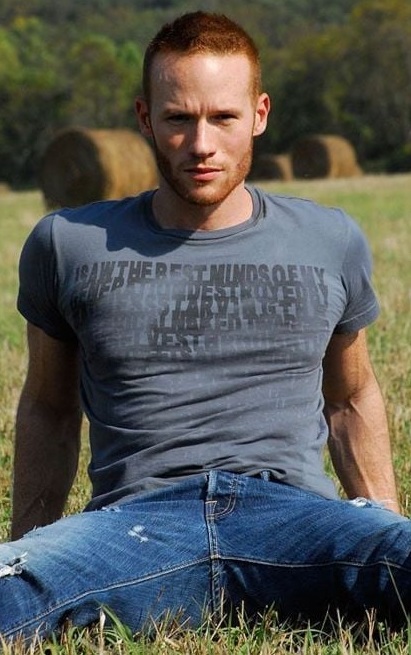

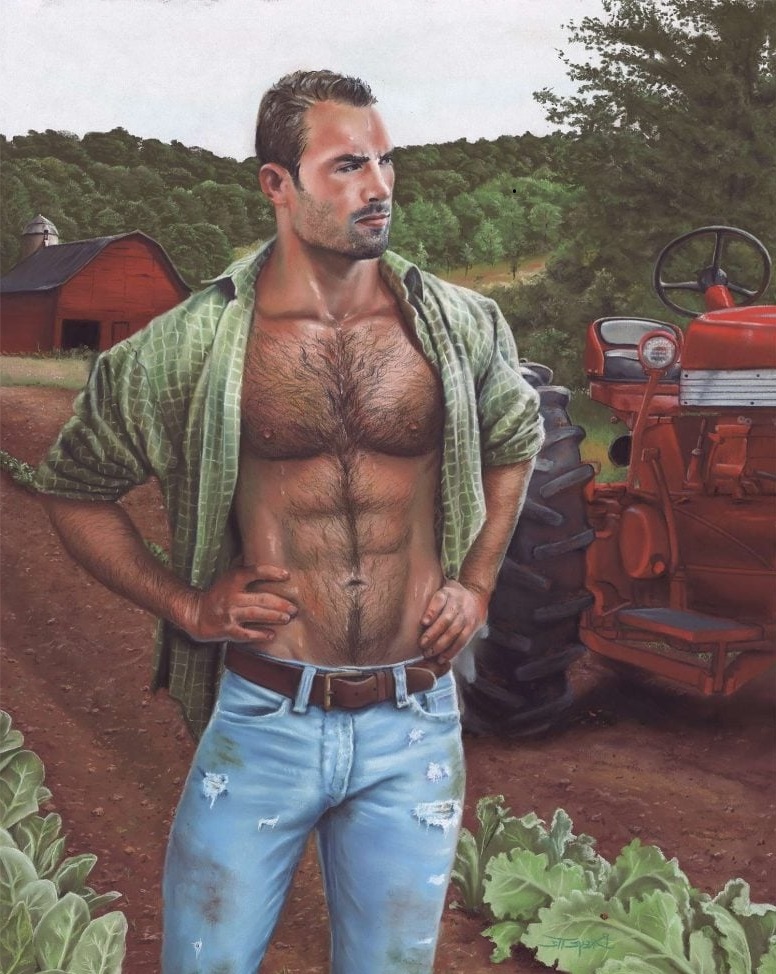

LGBTQ farmers,

ranchers, cowboys,

and cowgirls. They

go fly fishing,

mudding, hunting,

and square dancing.

You may not be aware

that there are gay

rodeos and gay chili

cook-offs and gay

country music

singers.

Queer Survival in Mississippi and the

Bars That Saved Us

Sweet Pride Alabama: Celebrating LGBTQ

lives in the Deep South

Small Towns Across the US Celebrate Pride

Memphis Pride: What Queer Joy Looks Like in the South

Y'all Means All (Queer Eye): Miranda

Lambert

Christopher Macken: Growing Up Gay in the South

TV Series: "Farming for Love" Features Gay Farmer

Kirkland Douglas

Ollie Schminkey & Wyatt Fleckenstein:

Small Towns

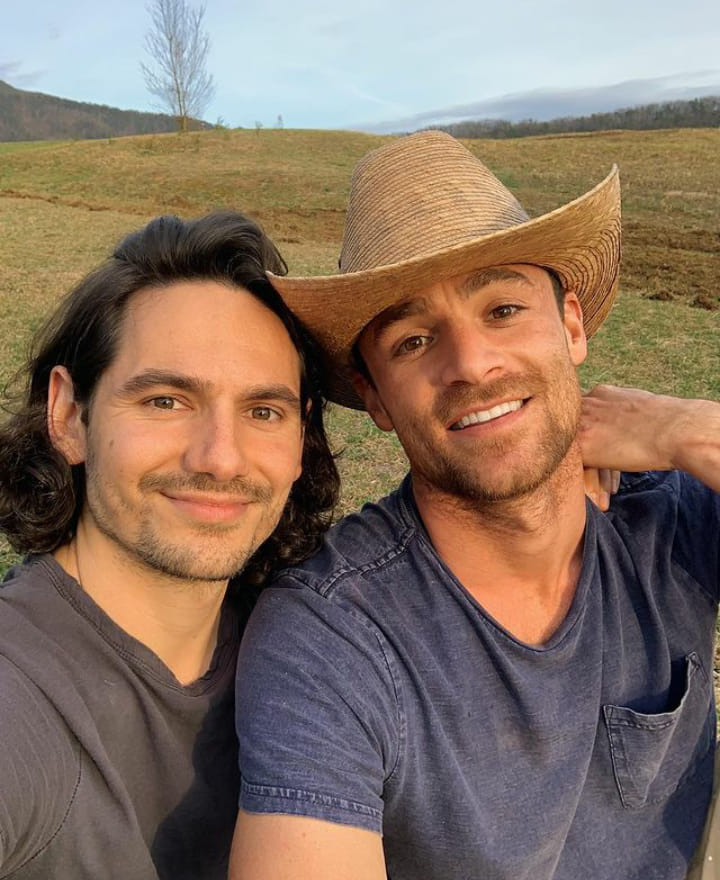

Singer Ty Herndon Marries Alex Schwartz

In A 'Country Chic' Tennessee Wedding

LGBTQ Pride Celebrations Held in Rural or

Small-Town America

Invisible Histories

Project: Gay Southern History

Christopher Macken: Growing Up Gay in the South

Central Alabama Pride 2025

Angel Olsen: Big Time

Look

up a rural pride event this summer. Go

to it. And lend your support to the

LGBTQ folks who live in the country.

Clap at the little parade, consume large

quantities of barbeque, dance in a

barn, make out with a hot

cowboy or cowgirl, encourage a teen, hug a

drag queen, listen to an elder, give

money to a PFLAG chapter.

LGBTQ people live in rural America, in

little towns all across Appalachia. They

work there, go to school, own property,

pay taxes, raise families, attend

churches, shop and donate to charity.

They don’t have a lot of gay bars, LGBTQ

sports clubs, drag shows or

neighborhoods where they can hold hands

with their partners. Nonetheless, they

live in these rural settings. They have

friends and families there. They are

part of the community. And sometimes,

depending on the attitudes of the

locals, they do it under a great

deal of stress.

Oftentimes, rural mindsets do not take

well to LGBTQ issues. People who live in

small southern towns tend to be more

traditional, more conservative in their

perspectives. Their worldview is

typically not affected by outside

influences and often colored by their religious

upbringing and conventional mores. So, a

gay country boy is a contradiction in

terms.

On the other hand, it may be surprising

for you to learn that there is

some degree (and in some cases, a great

degree) of openness and acceptance for

the LGBTQ community in the larger

metropolitan areas in the south, like

Atlanta, Nashville, Birmingham, Houston,

Orlando, and New Orleans. While they are located in

the conservative south, these are not

small towns or rural areas by any

definition. Many of these urban centers

host a thriving LGBTQ community.

Understanding Southern Culture

DC Rawhides: Country Music Dancing

Nature Doesn’t Care if You’re Gay or Straight: Meet the

Gay Farmers Queering Agriculture

Ohio Teen Starts LGBTQ Organization in

Tiny Rural Village

Birmingham Pride: Central Alabama Knows

How to Party

Info: LGBTQ Southern, Grassroots, Local, Community

Projects

Finding LGBTQ Community in

the Rural South

Charlotte Pride Parade1

LGBTQ Nation: Rural Pride Events

Men Reveal What It’s Like to Be Gay in Isolated Rural

Areas

Pride Source: Rural Americans Are LGBTQ Too

Being LGBTQ in the Deep

South

LGBTQ Country Music Stars Who Are Out and Proud

Country Queers: Joy and Pain of Rural LGBTQ Life

Leslie Jordan: Southern Gay

Fabulous Chicken

Coop

Central Alabama

Pride 2025

Redneck Lesbo by Jennifer

Corday

Country Queers: Oral Histories

In Appalachia, Hell Hath No Fury Like a Trans Goth With

a Banjo

Being Gay in Tennessee

Wasn't Always Easy

Advocate:

LGBTQ People of Color in Rural America

F150 by Dixon

Dallas

Josh Burford: Chronicler of Southern

LGBTQ History

GLAAD

Stories: LGBTQ Life in the South

Farming is

Tough: Being LGBTQ Makes it Tougher

Southeast US: Dangerous for

Trans People

Men Reveal What It’s Like to Be Gay in

Isolated Rural Areas

Growing Up in a Small

Town Made This Couple Realize Not All

Gay People Dream of Big City Life

LGBTQ

Community is Transforming the South

Small Town in

Ohio Has Its

First Pride

Celebration and

the Community

Loved it

And gearing up

for their second

year!

In the bucolic,

conservative,

small town of

Broadview

Heights, Ohio

(south of

Cleveland, north

of Akron and

right next door

to the

spectacular

Cuyahoga Valley

National Park)

Jennifer Speer

and fellow

members of

Brecksville/Broadview

Heights Pride

put on their

town’s very

first “Pride

Fest” in June

2023.

“We didn’t know

what to expect,”

Speer, who

serves as

president of the

group of LGBTQ

community

members and

allies. The

mission of BBH

Pride, Speer

says, “is to

promote

awareness,

instill

acceptance,

promote

inclusiveness,

and foster a

welcoming

community for

all LGBTQ

individuals. We

provide

education,

workshops,

fellowship,

meetings, and

special events,

all with the

goal of

establishing

empathy,

respect, and

celebration of

the LGBTQ

community.”

Christopher

Macken: Growing

Up Gay in the

South

Sweet Pride

Alabama:

Celebrating

LGBTQ lives in

the Deep South

Small Towns

Across the US

Celebrate Pride

Memphis Pride:

What Queer Joy

Looks Like in

the South

LGBTQ Country

Music Stars Who

Are Out and

Proud

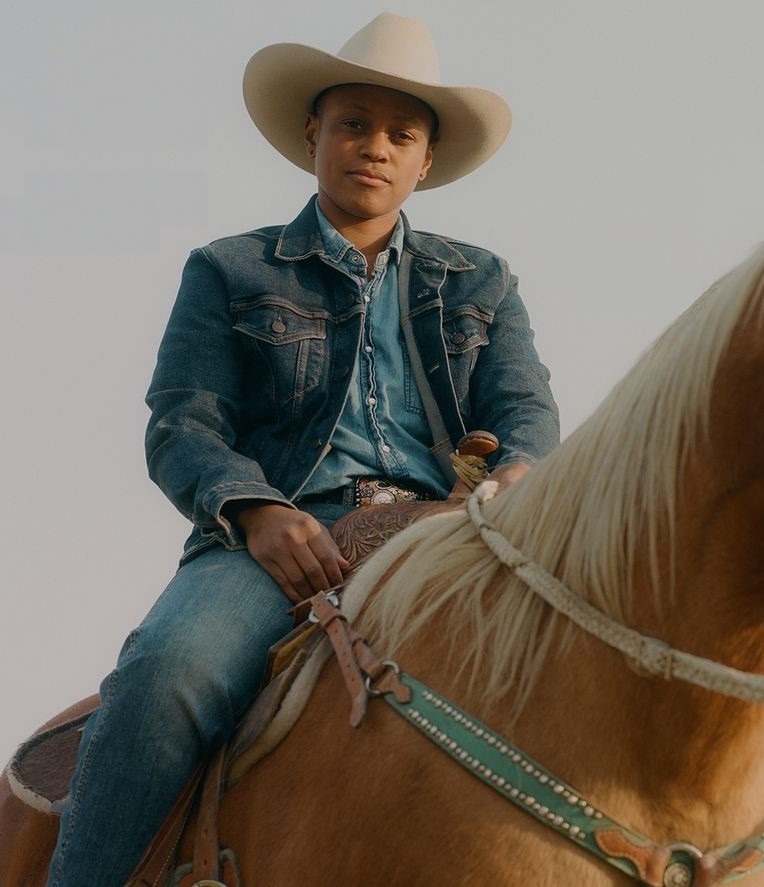

TV Series:

"Farming for

Love" Features

Gay Farmer

Kirkland Douglas

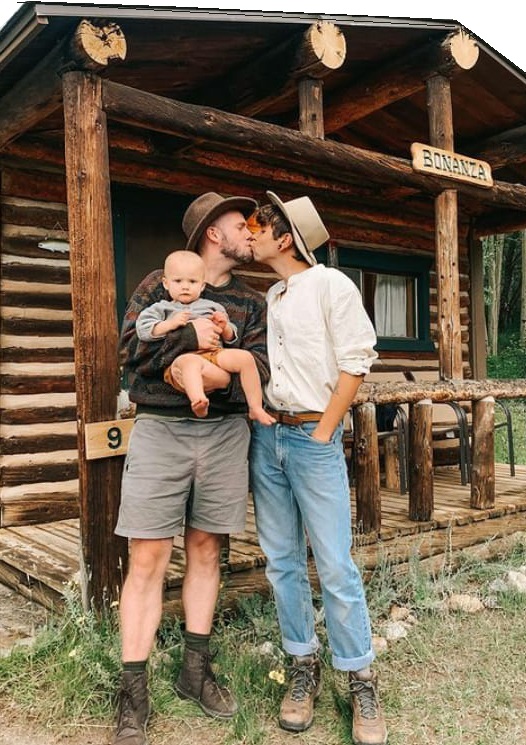

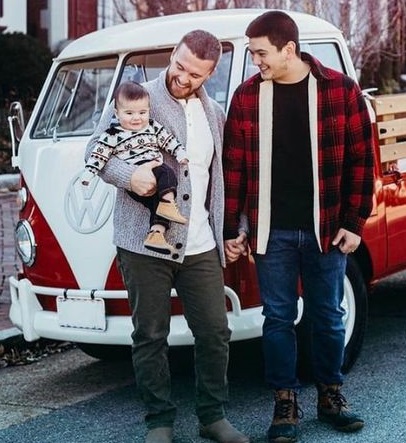

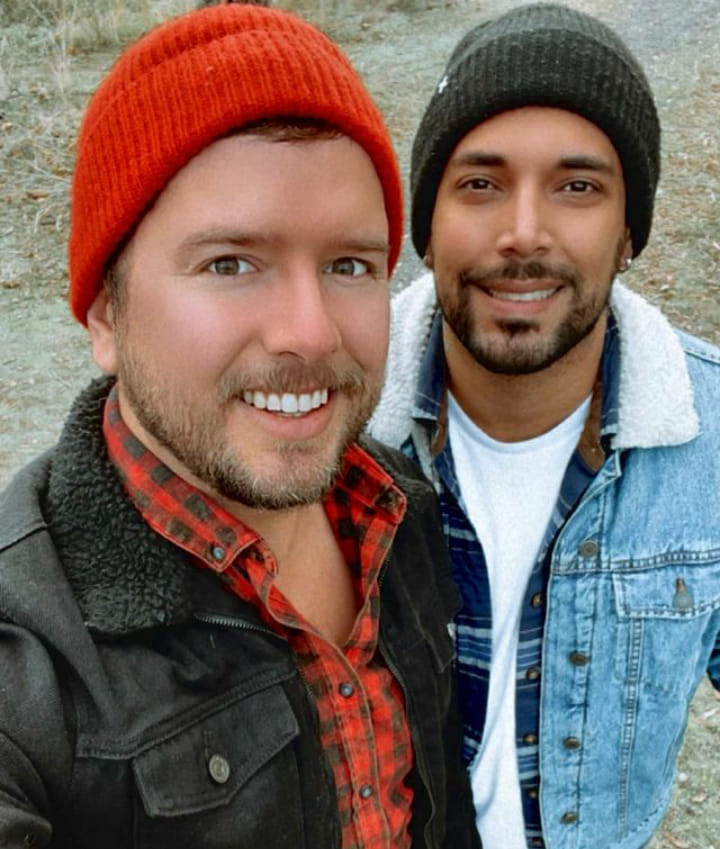

Matt and Blue: Gay Family Living in a Small Town

Small Town Gay Pride Parade

Not As Bad You You Think:

LGBTQ People in Rural America

International Gay Rodeo

Association

Country People: Gay Short

Film

Unapologetically

Southern and

Queer: Invisible

Histories

Project

Christopher

Macken: Growing

Up Gay in the

South

Fabulous Chicken

Coop

Whether or not

their more

conservative

neighbors would

tolerate a

public display

of LGBTQ,

“empathy,

respect, and

celebration” was

an open question

for the group in

the months

leading up to

Pride Fest.

“This was our

first annual

event and it was

being held in a

conservative

community,”

Speer says. “Our

goal was to have

250 people — but

we had 750! It

was a huge

success!”

“Even our local

police chief

gave it high

praise,” Speer

adds, “and our

local media

named BBH Pride

Fest one of the

best

celebrations in

Northeast Ohio,

and this was our

very first

event!”

Along with “a

huge outpouring

of support,

donations, and

sponsorships,”

however, BBH

Pride also faced

backlash, Speer

says. “We

have had to

fight adversity

to bring our

organization to

this community,

and we continue

that fight every

day. We’re

getting ready to

host our 2nd

annual Pride

Fest and a small

anti-LGBTQ

faction is

fighting us. But

we are moving

forward and the

event is on as

planned. We

cannot wait to

hit Pride Fest

again in June 8

2024!”

[Source: Greg

Owen, LGBTQ

Nation, May

2024]

Birmingham

Pride: Central

Alabama Knows

How to Party

DC Rawhides:

Country Music

Dancing

Queer Survival

in Mississippi

and the Bars

That Saved Us

Nature Doesn’t

Care if You’re

Gay or Straight:

Meet the Gay

Farmers Queering

Agriculture

Ohio Teen Starts

LGBTQ

Organization in

Tiny Rural

Village

Small Town in Ohio Has Its First Pride Celebration and

the Community Loved it

Jennifer Lawrence Honors Orville Peck at

the GLAAD Media Awards

Country Star Ty Herndon Marries Boyfriend

in Tennessee Wedding

Central Alabama Pride 2025

In Appalachia, Hell Hath No Fury Like a Trans Goth With

a Banjo

Better This Way: Country Song by Doug Strahm

Wild West: Much Gayer Than You Think

Small Town in South Dakota: Champion for Its LGBTQ

Neighbors

Building a More LGBTQ Inclusive South

Pride Source: Real Gay Cowboys

Dancing in the Living Room: Country Song by Cameron Hawthorn

Finding the LGBTQ

Community in the Rural South

Lesbian Farmer Taylor Blake and Emmanuel

the Emu

The

out and proud lesbian farmer in South

Florida started creating content for

Knuckle Bump in January 2022, but it

wasn’t until Emmanuel took the screen

that the TikTok page blew up. Now,

Knuckle Bump Farms is seemingly an

Emmanuel fan page.

The dynamic duo stars in a variety of

videos that show off their best-friend

bond. They hold hands, tell each other

jokes, and even cuddle in the afternoon

sun, making one thing clear: An emu

really is a gal’s best friend.

Taylor Blake and Emmanuel the Emu

Internet Fans Have Fallen in Love with

Emmanuel the Emu

Taylor and Her Emu Find Fame

Don't Do It Emmanuel

Emmanuel the Emu and Lesbian Farmer

Taylor Blake Drop by The Tonight Show

Taylor Blake: Facebook

Blake shared her love for the nearly

six-foot-tall bird in an Emmanuel

appreciation post on Instagram. She

wrote: "All I’ve ever wanted was to

spread joy like wildfire, I feel like

all my dreams are coming true. I can’t

wait to tell my future children all

about how an emu changed my life.”

Knuckle Bump Farms primarily focuses on

miniature cattle. But it also features

two obnoxious emus: Emmanuel and Ellen.

Don’t get any wild ideas, folks. Blake

says that the two are not an item.

“Ellen and Emmanuel hate each other,”

Blake shared in a TikTok comment

section. She also shared the Emmanuel

"hasn’t fully come out yet" but she's

“pretty sure he’s gay.”

Born

in Texas, Blake is 29 years old. She

currently lives in South Florida with

her girlfriend Kristian Haggerty.

Birmingham

Pride: Central

Alabama Knows

How to Party

TV Series:

"Farming for

Love" Features

Gay Farmer

Kirkland Douglas

The Aunties:

Working Harriett

Tubman's Farm

Tyler Childers -

In Your Love

I Lassoed Queer Joy in a Rodeo-Loving

Town

Building a More LGBTQ Inclusive South

Tyler and Todd: Living Off

the Grid

Charlotte Pride Parade2

Photographer Luke Gilford Finds Queer Joy

in Queer Cowboys

LGBTQ People: Fundamental

Part of the Fabric of Rural Communities

Interview: Married Mountain Men of West Virginia

Hometown: Country Song by Brandon Stansell

Over Half

of LGBTQ Southerners Say Parents Tried

to Repress Their Identity

Christopher

Macken: Growing

Up Gay in the

South

Queer

in the Country

Why do

some LGBTQ Americans prefer rural life

to urban gayborhoods? Pop

portrayals of LGBTQ Americans tend to

feature urban gay life, from Ru Paul’s

“Drag Race” and “Queer Eye” and “Pose.”

But not all gay people live in cities.

Demographers estimate that 15% to 20% of

the United States’ total LGBTQ

population – between 2.9 million and 3.8

million people – live in rural areas.

These millions of understudied LGBTQ

residents of rural America are the

subject of my latest academic research

project. Since 2015 I have conducted

interviews with 40 rural LGBTQ people

and analyzed various survey data sets to

understand the rural gay experience. My

study results, now under peer review for

publication in an academic journal,

found that many LGBTQ people in rural

areas view their sexual identity

substantially differently from their

urban counterparts – and question the

merits of urban gay life.

Understanding

Southern Culture

Ohio Teen Starts

LGBTQ

Organization in

Tiny Rural

Village

Sweet Pride

Alabama:

Celebrating

LGBTQ lives in

the Deep South

Small Towns

Across the US

Celebrate Pride

Memphis Pride:

What Queer Joy

Looks Like in

the South

LGBTQ Country

Music Stars Who

Are Out and

Proud

Small Town in

Ohio Has Its

First Pride

Celebration and

the Community

Loved it

Country Singer

Chris Housman:

Guilty as Sin

Ever Been to the Gay Rodeo?

Central Alabama Pride 2025

All American Boy: Country Song by Steve Grand

Patrick Haggerty: Singer Who Recorded

First Gay Country Songs Dies at 78

Gay Race Car Driver Zach Herrin Makes

NASCAR Debut

LGBTQ and Rurality

Lesbian Farmer's Emu Becomes Internet

Sensation

Lavender Country: Self-Proclaimed Screaming Marxist

Bitch of Country Music

Rednecks for Black Lives:

Southerners Fight for Racial Justice

Info: LGBTQ Southern, Grassroots, Local, Community

Projects

Fabulous Chicken

Coop

Easy come, easy go

The

standard narrative of rural gay life is

that it’s tough for LGBTQ kids who flee

their rural hometowns for iconic urban

“gayborhoods” like Chicago’s Boystown or

the Castro in San Francisco – places

where they can find love, feel “normal”

and be surrounded by others like them.

But this rural exodus story is

incomplete. Most research, mine

included, suggests that many rural LGBTQ

folks who once sought refuge in the big

city ultimately return home.

To the extent that American pop culture

portrays rural LGBTQ adult life, the

focus is on their isolation – think

“Brokeback Mountain” or “Thelma &

Louise.” The gay protagonists of these

films are lonely, seldom able to express

their sexual selves.

But my analysis of a 2013 Pew Survey of

LGBTQ Americans (the latest available

comprehensive national survey data on

this population) showed that LGBTQ rural

residents are actually more likely to be

legally married than their urban

counterparts – 24.8% compared with

18.6%. This aligns with what I’ve heard

in interviews. The rural LGBTQ people I

spoke with placed a high value on

monogamy – on what many of them consider

a “normal” life.

Those who returned home from urban

gayborhoods also told me they found gay

city living rarely delivered on its

promises of companionship and inclusion.

Many said they had experienced rejection

while trying to date or develop a social

circle. And they had missed the charm of

small-town life.

Birmingham

Pride: Central

Alabama Knows

How to Party

DC Rawhides:

Country Music

Dancing

Queer Survival

in Mississippi

and the Bars

That Saved Us

Nature Doesn’t

Care if You’re

Gay or Straight:

Meet the Gay

Farmers Queering

Agriculture

In Appalachia,

Hell Hath No

Fury Like a

Trans Goth With

a Banjo

LGBTQ Country

Artists You Need

to Listen to

Immediately

Gay Rodeo: Hall of Fame

Memphis Pride: What Queer Joy Looks Like in the South

TV Series: "Farming for Love" Features Gay Farmer

Kirkland Douglas

LGBTQ Pride in Rural Missouri

Orville Peck & Willie Nelson: Cowboys Are Frequently

Secretly Fond Of Each Other

Men Reveal What It’s Like to Be Gay in Isolated Rural

Areas

Good Looking by Dixon Dallas

Southern Queers: New Study Reveals the

Reality of LGBTQ People in the South

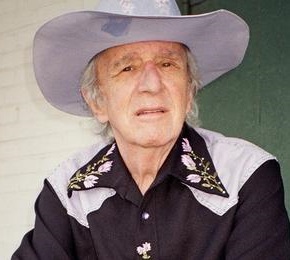

Lavender Country's Patrick

Haggerty was Embraced as Gay Country Music's Radical

Elders

Jennifer

Lawrence Honors

Orville Peck at

the GLAAD Media

Awards

No escape

The rural LGBTQ people I interviewed

seemed to place less importance on being

gay than their urban communities had.

Downplaying their sexual or gender

identities, many emphasized other

aspects of themselves, such as their

involvement in music, sports, nature or

games. They rejected an urban gay

culture that they felt was shallow and

overly focused on gayness as the

defining feature of life.

One married 35-year-old described his

big-city life this way: “Going to bars,

bitching about how bad we have it in

comparison to other cities, or judging

people based on what they are wearing.”

Such comments call into question certain

assumptions of the contemporary gay

rights movement, including that

“gayborhoods” are the pinnacle of gay

life and that rural America is no place

for LGBTQ people.

This may be less true, though, for Black

and Latino LGBTQ people. A 2019 report

on rural LGBTQ Americans found that

“discrimination based on race and

immigration status is compounded by

discrimination based on sexual

orientation, gender identity and gender

expression.”

Andrew Mitch:

Back Home Boy

Sweet Pride

Alabama:

Celebrating

LGBTQ lives in

the Deep South

Small Towns

Across the US

Celebrate Pride

Charlotte Pride Parade1

Christopher Macken: Growing Up Gay in the South

Pride Source: Rural Americans Are LGBTQ Too

Country Queers: Joy and Pain of Rural LGBTQ Life

International Gay Rodeo Association: John King Interview

PFLAG: Experiences of

LGBTQ Students in Small Rural Towns

In the Face of Discrimination: LGBTQ Farmers are Hopeful

Info: LGBTQ

Southern,

Grassroots,

Local, Community

Projects

Small Town in

Ohio Has Its

First Pride

Celebration and

the Community

Loved it

LGBTQ Country

Music Stars Who

Are Out and

Proud

Christopher

Macken: Growing

Up Gay in the

South

Fabulous Chicken

Coop

While I found no direct evidence that

LGBTQ people of color were less likely

to return to rural areas, the many

difficulties of rural living for this

population may partly explain why most

of my interview subjects were white,

despite my efforts to identify a more

diverse pool.

But, as

some of the people I interviewed

reminded me, no matter where they lived

they would not be fully accepted. “As a

trans person, I’m always going to have

to deal with people discriminating

against me,” one woman said. Living in a

rural locale with an active local music

scene let her focus on aspects of her

identity that were more important to her

than her gender identity.

For some LGBTQ Americans, then, rural

life allows them to more fully express

themselves. Given the variety of issues

facing LGBTQ Americans, from health care

access to work problems, the rural world

is not an escape from discrimination.

But neither are urban areas. One lesbian

from Kansas recalled attending a

fundraiser for the Human Rights Campaign

(the country’s most prominent LGBTQ

advocacy group) in Washington, DC, where

a high-ranking member of the

organization shook her hand and said,

“Thank you so much. We need you out

there in Kansas badly!” To this

the Kansan replied, “Thank me? I’ve been

there my whole life. We are the ones who

need you in Kansas. You are the ones who

forgot about us!”

[Source: Christopher T. Conner,

Assistant Professor of Sociology,

University of Missouri-Columbia, March

2021]

Birmingham

Pride: Central

Alabama Knows

How to Party

The Aunties:

Farmers Donna

Dear and

Paulette Greene

Continue Harriet

Tubman’s Legacy

Growing Up Gay in the Christian South

Ohio Teen Starts

LGBTQ

Organization in

Tiny Rural

Village

Pride Source: Real Gay Cowboys

Tyler

Childers - In Your Love

Country Star Ty Herndon Marries Boyfriend in

Tennessee Wedding

I Lassoed Queer Joy in a Rodeo-Loving Town

Patrick Haggerty: Singer

Who Recorded First Gay Country Songs

Dies at 78

Country Singer Sam Williams, Son of Hank

Williams Jr, Comes Out as Gay

Ever Been to the Gay Rodeo?

Young Girl Growing Up Gay

in a Conservative Hometown

F150 by Dixon Dallas

Gay

Life in Rural America

“I hope that somewhere in Small

Town, USA, a 15-year-old kid looks to me

as a role model the way I looked at the

Indigo Girls and Elton John as role

models.”

-Brandi Carlile

Millions of lesbian, gay, bisexual,

transgender, and queer people live in

rural areas of the United States —

largely by choice, according to a report

released earlier this month by the LGBTQ

think tank Movement Advancement Project.

MAP’s report estimates between 2.9

million and 3.8 million lesbian, gay,

bisexual, transgender, and queer people

live in rural America, comprising

approximately 3 to 5 percent of the

estimated 62 million people who live in

rural areas.

“We so often overlook that LGBTQ people

live in rural communities,” Logan Casey,

a MAP policy researcher and one of the

report’s lead authors, said. “But being

LGBTQ doesn’t mean you want to go live

in a coastal city.” The report notes

that LGBTQ people are drawn to rural

areas for many of the same reasons as

their heterosexual counterparts —

proximity to family, a tight-knit

community and a connection to the land.

However, the report also found rural

LGBTQ communities are uniquely affected

by the “structural challenges and other

aspects of rural life,” which it notes

could “amplify the impacts of both

rejection and acceptance.”

Country Singer Chris Housman: Guilty as Sin

Queer in

Rural America

Queer Survival in Mississippi and the

Bars That Saved Us

Memphis Pride: What Queer Joy Looks Like in the South

Sharon Van Etten & Angel Olsen: Like I

Used To

Emmanuel the Emu and Farmer Taylor Blake

Drop by The Tonight Show

Black and

Gay in Birmingham

Jennifer Lawrence Honors Orville Peck at

the GLAAD Media Awards

Info: LGBTQ Southern, Grassroots, Local, Community

Projects

Son of a

Preacher Man: Country Song by Tom Goss

Good Looking by Dixon Dallas

Unapologetically

Southern and Queer: Invisible Histories Project

LGBTQ Country Artists You Need to Listen to

Immediately

DC Rawhides: Country Music Dancing

The report found the social and

political landscape of rural areas makes

LGBTQ people “more vulnerable to

discrimination. Public opinion in rural

areas is generally less supportive of

LGBTQ people and policies, and rural

states are significantly less likely to

have vital nondiscrimination laws and

more likely to have harmful,

discriminatory laws,” the report states.

Simple, everyday actions can also be

fraught, especially for transgender

people. According to the report, 34

percent of trans people report

discrimination on public transportation

and 18 percent report harassment at a

gym or health club. These numbers apply

to rural and urban residents, but

Casey’s research indicates that lack of

alternative options and the importance

of public spaces in small, tight-knit

communities can make harassment harder

to bear in rural areas.

The report also notes the geographic

distance and isolation of rural areas

can present challenges for LGBTQ people.

“If someone experiences discrimination

at a doctor’s office, school or job,

it’s less likely there’s another option

close by,” Casey explained.

The report also found those in rural

areas have less access to LGBTQ-specific

resources. Fifty-seven percent of LGBTQ

adults in urban areas have access to an

LGBTQ health center, while only 11

percent of those in rural areas do. And

when it comes to senior services, almost

half of LGBTQ adults have access to

LGBTQ senior services, compared to just

10 percent of their rural counterparts.

Andrew Mitch: Back Home Boy

Understanding Southern Culture

In Appalachia, Hell Hath No Fury Like a Trans Goth With

a Banjo

Small Towns Across the US Celebrate Pride

Y'all Means All (Queer

Eye): Miranda Lambert

LGBTQ Country Music Stars Who Are Out and Proud

TV Series: "Farming for Love" Features Gay Farmer Kirkland

Douglas

Small Town in Ohio Has Its First Pride Celebration and the

Community Loved it

Fabulous

Beekman Boys: Gay Green Acres

Out Country Star Ty Herndon Ties The Knot In 'Country

Chic' Wedding

Growing Up

Gay in Appalachia

Southern Queers: New

Study Reveals the Reality of LGBTQ

People in the South

Gay Prom in Birmingham

I Lassoed Queer Joy in a Rodeo-Loving

Town

Orville Peck & Willie Nelson: Cowboys Are Frequently

Secretly Fond Of Each Other

Finding

LGBTQ Community in the Rural South

Lesbian

Farmers: Redefining Rural America

Clearly

Gay in Small Town Alabama

There was also an urban-rural divide

when it comes to the school climate for

LGBTQ youth. Almost 60 percent of LGBTQ

youth in urban areas reported having a

gay-straight alliance club in their

school, compared to just 36 percent of

LGBTQ youth in rural areas.

The smaller populations of rural areas

can also complicate matters for LGBTQ

people, because they are more likely to

stand out. This can make them more

vulnerable to discrimination but also

keep problems they face under the radar.

One of the biggest challenges the report

identifies is health care. Fifty six

percent of gay, lesbian and bisexual

people across the country reported at

least one instance of discrimination or

patient profiling in a health care

setting. According to statistics cited

in the report, more than 40 percent of

non-metropolitan LGBTQ people said if

they were turned away by their local

hospital, it would be “very difficult”

or “not possible” for them to find an

alternative, compared to 18 percent of

the general LGBTQ population, according

to a statistic cited in the report.

We Live Here: the Midwest

Miranda Lambert: If I Was a Cowboy

Christopher Macken: Growing Up Gay in the South

Country Singer Sam Williams, Son of Hank Williams Jr,

Comes Out as Gay

Y'all Means All (Queer Eye): Miranda

Lambert

NBC News Report: Gay in Rural America

LGBTQ Community is

Transforming the South

Country Singer Chris Housman: Guilty as Sin

Charlotte Pride Parade2

Young Girl Growing Up Gay in a

Conservative Hometown

Emmanuel the Emu and Farmer Taylor Blake Drop by The

Tonight Show

Christopher Macken: Growing Up Gay in the South

DC Rawhides: Country Music Dancing

Nature Doesn’t Care if You’re Gay or Straight: Meet the

Gay Farmers Queering Agriculture

Country People: Gay Short

Film

Good Looking by Dixon

Dallas

Fabulous Chicken

Coop

Transgender people often struggle to

find health care providers knowledgeable

about gender-affirming care and are more

likely to have such care denied by their

insurance provider. Trans people of

color often face the added burden of

providers with a lack of cultural

competency for their community. Trans

people are also 15 percent more likely

to have transition-related surgery

denied by their insurance if they live

in a rural area.

While challenges for LGBTQ people can be

“amplified” in rural areas, the report

also found bright spots for lesbian,

gay, bisexual, transgender and queer

people living in non-metropolitan

communities. Same-sex couples and LGBTQ

individuals are raising children in

rural areas at higher rates than urban

areas. Some LGBTQ people feel safer in

rural areas than urban areas.

While

social conditions in the area are

changing, there are still legal and

policy hurdles. “LGBTQ people in rural

areas are disproportionately harmed by

the lack of protections and the presence

of discriminatory laws,” the report

states. “The current policy landscape

demonstrates the clear and urgent need

for federal and state nondiscrimination

protections for LGBTQ people.”

[Source: Avichai Scher, NBC News, April

2019]

Sweet Pride Alabama: Celebrating LGBTQ

lives in the Deep South

Jennifer Lawrence Honors Orville Peck at

the GLAAD Media Awards

The Aunties: Working Harriett Tubman's Farm

Ohio Teen Starts LGBTQ Organization in

Tiny Rural Village

Country Star Ty Herndon Marries Boyfriend

in Tennessee Wedding

Lavender Country's Patrick

Haggerty was Embraced as Gay Country Music's Radical

Elders

Gay Race Car Driver Zach Herrin Makes

NASCAR Debut

Country Singer Sam Williams, Son of Hank Williams Jr,

Comes Out as Gay

Lesbian Farmer's Emu Becomes Internet

Sensation

Pride Source: Rural Americans Are LGBTQ Too

Country Queers: Joy and Pain of Rural LGBTQ Life

LGBTQ Pride Festivals in Rural Canada

Over Half

of LGBTQ Southerners Say Parents Tried

to Repress Their Identity

DC Rawhides: Country Music Dancing

Country

Teens

Memphis Pride:

What Queer Joy

Looks Like in

the South

Good Looking by

Dixon Dallas

Point of

Pride: How to Be Queer in a Small Town

Patrick Haggerty: Singer

Who Recorded First Gay Country Songs

Dies at 78

Farming is

Tough: Being LGBTQ Makes it Tougher

Queer in

Rural America

Tyler Childers - In Your Love

Info: LGBTQ Southern, Grassroots, Local, Community

Projects

Time: Country Song by Steve Grand

Matt and Blue: Southern

Boys

LGBTQ Nation: Lesbian and

Trans Hillbillies Taking Over Rural America

Being LGBTQ in the Deep

South

Gay Rodeo History

LGBTQ Institute: Southern

Survey

LGBTQ Country Artists You Need to Listen

to Immediately

Growing Up in a Small Town Made This

Couple Realize Not All Gay People Dream of Big City Life

Southern LGBTQ Voters

According

to a recent study, a huge number of

Southern LGBTQ people registered to vote

in the 2020 presidential election. Queer

voters in this conservative region

appear very motivated to vote, according

to findings.

Recent findings indicate Southern LGBTQ

voters could make a significant impact

on the 2020 election, with states like

Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas in

play. The Campaign for Southern Equality

and Western North Carolina Community

Health Services released a report this

week about LGBTQ Southerners’ voting

behaviors and beliefs. The survey

queried over 5,600 participants across

the South last year.

There are about 9 million LGBTQ voters

in the US, according to the Williams

Institute. Southern states hold about 37

percent of the US population. One of the

key findings involved voter

participation and enthusiasm. Nearly 92

percent of those who participated in the

study were registered to vote. Those

numbers are significantly higher than

that of the general U.S. population,

with about 79 percent registered.

Researchers also asked participants

about their experience with physical or

emotional abuse and found that those

with a history of such trauma were less

likely to be registered than those who

did not. Transgender people and those

with lower incomes were also less likely

to be registered than cisgender people

and those with more money.

[Source: Neal Broverman, Advocate, Nov

2020]

LGBTQ Ohioan Strums His Way to Pop Country Success and

Trailblazing Authenticity

Photographer Luke Gilford Finds Queer Joy

in Queer Cowboys

Country People: Gay Short

Film

LGBTQ and Rurality

LGBTQ Country Music Stars Who Are Out and Proud

Unapologetically

Southern and Queer: Invisible Histories Project

Research on Rural LGBTQ

People of Color

LGBTQ Pride Celebrations Held in Rural or

Small-Town America

Queering the Redneck

Riviera

Advocate: Champions of

Pride from the South

F150 by Dixon Dallas

LGBTQ Nation: Lesbian and

Trans Hillbillies Taking Over Rural America

Not As Bad You You Think:

LGBTQ People in Rural America

Being LGBTQ in the Deep

South

Southern Queers: New Study Reveals the

Reality of LGBTQ People in the South

Finding the LGBTQ

Community in the Rural South

I Lassoed Queer Joy in a Rodeo-Loving Town

Country Queers: Oral Histories

Cottagecore Lesbians

Longing to escape to

the countryside with your queer girlfriend? You're not

alone. If you're on social media platforms like TikTok,

Tumblr and Pinterest, you've likely noticed the "cottagecore"

trend that's getting popular with queer women and

femmes. All at once, everyone seems to want to quit

their jobs and run off to upstate Vermont to pick

apples, raise chickens, and live their best

woman-loving-woman life.

It's caught on so much that the The New York Times

published a feature about it in March 2020. "Take modern

escapist fantasies like tiny homes, voluntary

simplicity, forest bathing and screen-free childhoods,

then place them inside a delicate, moss-filled

terrarium, and the result will look a lot like

cottagecore," says writer Isabel Slone.

The cottagecore aesthetic, however, is rooted in

real-world issues like climate change, the global

pandemic, and safe spaces for LGBTQ people.

Cameron Hawthorn: Oh Hot

Damn!

This Gorgeous Beach Town Is the Best

Gaycation in New England

Growing Up Gay in the Country

Queer Survival in Mississippi and the

Bars That Saved Us

Ohio Teen Starts LGBTQ Organization in

Tiny Rural Village

Slow Down: Country Song by Brandon Stansell and Ty

Herndon

LGBTQ and Rurality

Info: LGBTQ

Southern, Grassroots, Local, Community

Projects

Advocate: What is a

Cottagecore Lesbian?

Leslie Jordan: Southern Gay

Small Town in Ohio Has Its First Pride Celebration and

the Community Loved it

In Appalachia, Hell Hath No Fury Like a Trans Goth With

a Banjo

Christopher Macken: Growing Up Gay in the South

Nature Doesn’t Care if You’re Gay or Straight: Meet the

Gay Farmers Queering Agriculture

Essentially, the cottagecore aesthetic is images of

idealized life on a Western farm — cozy little houses

surrounded by gardens, fields of wildflowers, forest

glades, and cute farm animals. Occasionally you'll find

fantasy elements like fairies and goblins thrown in. If

you're into nostalgia, books, baking, teacups, prairie

dresses, flower crowns, picnic baskets, knitting,

embroidery, Hozier, ceramic frogs for some reason, and

strolling through farmers' markets, cottagecore might be

the movement for you.

Writer Katherine Gillespie of Paper Magazine puts it

this way: "The politics of cottagecore are thoughtfully

prelapsarian: what if we could go back to a time before

the planet was ravaged by industry, except with added

protections for marginalized queer communities? What if

we all lived like tradwives, minus the husbands?"

And, if you really identify with this idea, you can even

fly your own Pride flag (presumably in a very small

Pride parade through your imaginary rustic village),

with soft, natural, earth-tone shades.

Much of the cottagecore movement is actually a response

to people being dissatistfied with their hectic, crowded

lives in cities or suburbs, and the feelings of burnout

that come with it. Tired of the minimalist aesthetic

that's dominated interior design in the last ten years,

they're decorating their apartments with potted plants

and porcelain teacups, and taking comfort in

old-fashioned hobbies like arts & crafts and baking. The

NY Times calls it "an aspirational form of nostalgia

that praises the benefits of living a slow life."

[Source:

Christine Linnell, Advocate Magazine]

Queering Country

Music

Country Singer Chris Housman: Guilty as Sin

Country Star Ty Herndon Marries Boyfriend

in Tennessee Wedding

Country Music Artists Who Are Fam and

Belong On Your Playlist

Queer Artists Helping to Shake Up Country

Music

All American Boy by Steve Grand

Time by Steve Grand

Orville Peck & Willie Nelson: Cowboys Are Frequently

Secretly Fond Of Each Other

Queer Country Music Artists Fans Should Know About

Country Music Star TJ

Osbourne Comes Out as Gay

Jennifer Corday: Lesbian

Country Rocker

LGBTQ Country Music Stars Who Are

Out and Proud

Redneck Lesbo by Jennifer

Corday

Heartbeat by Jennifer

Corday

Dancing in the Living Room by Cameron Hawthorn

Take the Journey by Molly

Tuttle

Chely Wright: Return to the Grand Ole Opry

So

Small by Ty Herndon

LGBTQ Ohioan Strums His Way to Pop Country Success and

Trailblazing Authenticity

Andrew Mitch: Back Home Boy

Brooke Eden - Giddy Up!

Jennifer Lawrence Honors Orville Peck at the

GLAAD Media Awards

Slow Down by Brandon Stansell and Ty Herndon

Hometown by Brandon Stansell

Angel Olsen: Big Time

Angel Olsen: All The Good Times

Sharon Van Etten & Angel Olsen: Like I

Used To

Fink and Marxer: Queer

Bluegrass

Darling Cora by Amythyst

Kiah

Cowboys Are Frequently

Secretly Fond of Each Other by Ned Sublette

Good Looking by

Dixon Dallas

Leave This All Behind by Dixon

Dallas

F150 by Dixon Dallas

LGBTQ Country Artists You Need to Listen

to Immediately

Tyler Childers - In Your Love

Out Country Star Ty Herndon Ties The Knot In 'Country

Chic' Wedding

Same Old Country Love Song by Brian

Falduto

God Loves Me Too by Brian Falduto

Follow Your Arrow by Kasey Musgraves

Cameron Hawthorn: Oh Hot Damn!

Dixon Dallas: Good Lookin'

I'm Not in Love With You

by Justin Hiltner and Jon Weisberger

Son of a Preacher Man by

Tom Goss

Neon Cross by Jamie Wyatt

Wishing Well by Jamie

Wyatt

LGBTQ Country Music Stars Who Are Out and Proud

Cryin' These Cocksucking

Tears by Lavender Country

Justin Hiltner: Subversive

Twist on a Familiar Motif

Limp Wrist and a Steady Hand by My Gay Banjo

Country Boys in the City

by My Gay Banjo

Porch Pride: LGBTQ

Bluegrass and Roots Music

Better This Way by Doug Strahm

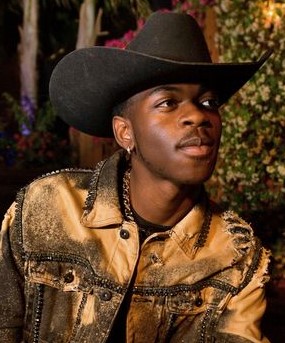

Old Town Road by Lil Nas X

Men Reveal What It’s Like to Be Gay in Isolated Rural

Areas

Ride Me Cowboy by Paisley Fields

If

She Ever Leaves Me by Highwomen

Ty

Herndon: What Mattered Most (Alternative Version)

Ty

Herndon: What Mattered Most (Original Version)

Dixon Dallas: Meet the Country Singer Going Viral for

his Explicitly Gay Ballad

LGBTQ-Friendly Country

Music Artists You Should Know About

LGBTQ

Rurality

Throughout history, rural spaces have

held multiple meanings and served

various functions for LGBTQ individuals

and communities, ranging from sites for

political organizing or sanctuary to

sites of repression and violence for

LGBTQ individuals.

Many popular representations of rurality

as well as anti-LGBTQ discourse citing

"protecting rural values" suggest these

communities intrinsically place a

heightened value on “traditional moral

standards.” Thus, communities in rural

areas are associated with a lower

tolerance for difference (including

non-binary gender expression and queer

sexuality) compared to urban

environments. Some queer-identified

individuals living in rural areas do

experience antagonism, oppression, and

violence matching the stereotypical

representation of what it means to be

queer in a rural community.

As of 2000, the US Census found that 46

million people (roughly 16% of the

nation's total population) live in areas

with population densities of 999 people

per square mile or fewer. Considering

the high number of individuals and the

small population density, the rural

population of the US exists across a

wide geographical area. Despite the

categorization based upon population

density, "the rural population is not

the same everywhere except in its

distinction of not being urban." The

variation within the category of rural

is reflected in the multiple, varied

experiences of queer-identified people

living in rural areas.

In popular depictions, rurality is often

portrayed as an inherently incompatible,

or even hostile, environment for

individuals who are not heterosexual

and/or cisgender. While this may be an

accurate contrast between some urban and

rural settings, there is significant

variation within each categorization

based on population density.

Understanding Southern Culture

Memphis Pride: What Queer Joy Looks Like in the South

Advocate:

Champions of Pride from the South

LGBTQ Ohioan

Strums His Way

to Pop Country

Success and

Trailblazing

Authenticity

Andrew Mitch:

Back Home Boy

TV Series:

"Farming for

Love" Features

Gay Farmer

Kirkland Douglas

The Aunties:

Farmers Donna

Dear and

Paulette Greene

Continue Harriet

Tubman’s Legacy

South

Florida Gay News: Queering the Redneck

Riviera

Huff Post:

Lesbian Farmers: Growing Rural America

Spend a Weekend in

Florida’s Most LGBTQ Friendly Small Town

Country Singer Sam Williams, Son of Hank

Williams Jr, Comes Out as Gay

Being Gay

and Lesbian in Appalachia

I Lassoed Queer Joy in a Rodeo-Loving

Town

How to Be Queer in

Country Music: The Story of Mya Byrne

Point of

Pride: How to Be Queer in a Small Town

Gay Farmers: Bilkurra Homestead

Conversation with Gay Fly Fisherman

Emmanuel the Emu and Farmer Taylor Blake

Drop by The Tonight Show

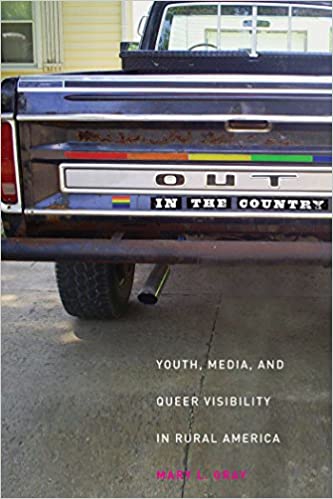

Rural/Urban Dichotomy and Visibility

Politics

Queer

regionalist scholars such as Mary Gray

have illustrated that organizing for

LGBTQ issues in the post-Stonewall US

has centered around a politics of

visibility. Within this political

framework, publicly claiming a minority

sexual orientation is viewed as

inherently political. Visibility

politics claim that, by making one's own

queerness visible, 'out' individuals

resist heteronormativity and the erasure

of non-heterosexual behaviors and

identities as well as illustrate to

their local, national, and global

communities that queer people exist and

need equal rights and protection under

the law. Therefore, visibility politics

view a public declaration of queer

identity as the primary road to

political liberation and equality for

queer communities.

Visibility politics also creates an

understanding of queer lives through the

metaphor of the closet (which Eve

Sedgwick terms the epistemology of the

closet). Within the epistemology of the

closet framework, LGBTQ persons are born

'in the closet' or with a repressed

sexuality until the catalytic moment of

'coming out' at which point they become

'out' or publicly queer. Regional

scholars have argued that the reliance

upon the epistemology of the closet and

visibility politics within US queer

activism is urban-centric, excluding and

erasing LGBTQ individuals and

communities in rural areas across the

globe. As the majority of

national-scale queer activism reliant on

visibility politics within the US

emerged from its major cities, this

ideology was "tailor-made for and from

the population densities; capital; and

systems of gender, sexual, class, and

racial privilege that converge in

cities." Mary Gray expands upon this

point in her book, Out in the

Country: Youth, Media, and Queer

Visibility in Rural America:

Christopher Macken: Growing Up Gay in the South

Huff Post:

Lesbian Farmers: Growing Rural America

Building a More LGBTQ Inclusive South

Queer Survival

in Mississippi

and the Bars

That Saved Us

Advocate:

LGBTQ People of Color in Rural America

Y'all Means All (Queer

Eye): Miranda Lambert

Ever Been to the Gay Rodeo?

Being Gay

and Lesbian in Appalachia

DC Rawhides:

Country Music

Dancing

Invisible

Histories Project: Gay Southern History

Photographer Luke Gilford

Finds Queer Joy in Queer Cowboys

Matt and

Blue: Southern Boys

Lesbian Farmer's Emu

Becomes Internet Sensation

Wishing

Well by Jamie Wyatt

LGBTQ

People: Fundamental Part of the Fabric

of Rural Communities

Lavender

Country's Patrick Haggerty was Embraced

as Gay Country Music's Radical Elders

"Metronormative epistemologies of

visibility privilege urban queer scenes.

The systemic marginalization of the

rural as endemically hostile and lacking

the cultural milieu necessary for a

celebratory politics of difference

naturalizes cities as the necessary

centers and standard bearers of queer

politics and representations. Along the

way all those not able, or inclined, to

migrate to the city are put at a notable

disadvantage not just by the material

realities of rural places but also by

the shortcoming of queer theory and

LGBTQ social movement in ways we have

only recently begun to explore."

US scholarship on queer life within

metropoles further perpetuates the

centrality of metronormative narratives

of queer life and identity. John

D'Emilio proposed a contradictory

connection between capitalism and

homosexuality. He argued that capitalism

emphasized the importance of family

units and reproduction as the primary

function of that unit. However,

simultaneously the anonymity of US

cities, a product of capitalist

development, enabled networks of

same-sex desiring individuals to form

and a homosexual community and shared

identity to emerge. George Chauncey is

another historian whose work centered on

queer life in urban centers. His book

Gay New York examined how gay life in

New York City formed around patterns of

congregation and habit. Both D'Emilio

and Chauncey highlight the ways that

urban environments distinctly, and

possibly uniquely, enable queerness.

Thus, their findings to some extent

reinforce a binary view of urban/rural

wherein urban is perceived as a space

for liberated, 'out' queer communities

while rural is a space for isolated,

'closeted' queer individuals.

Memphis Pride: What Queer Joy Looks Like in the South

Country Singer Chris Housman: Guilty as Sin

I Lassoed Queer Joy in a Rodeo-Loving

Town

Ki Ya Yah Yippee Ki Yay:

Thirst-Trapping Gay Cowboys

Being Gay

in Tennessee Wasn't Always Easy

Tyler Childers -

In Your Love

Info: LGBTQ

Southern,

Grassroots,

Local, Community

Projects

GLAAD

Stories: LGBTQ Life in the South

I'm Queer

and I'm Country

Southern Queers: New

Study Reveals the Reality of LGBTQ

People in the South

How to Be Queer in

Country Music: The Story of Mya Byrne

Fabulous

Beekman Boys: Gay Green Acres

Cameron Hawthorn: Oh Hot

Damn!

LGBTQ

Community is Transforming the South

This Tiny Michigan Town Is One of

America’s Best LGBTQ Destinations

Christopher Macken: Growing Up Gay in the South

Redneck

Lesbo by Jennifer Corday

Fabulous Chicken

Coop

Studies and fieldwork by contemporary

scholars prove the existence of queer

lives in rural areas and challenge a

systemic erasure of non-urban queer

life. In particular, scholars of the

American South and Midwest have written

on queer life in rural areas,

challenging the belief that rurality is

inherently not conducive to queer sexual

expression.

The presence of LGBTQ bars, bookstores,

and neighborhoods within

population-dense, urban areas makes the

presence of queer individuals and

communities more visible than in less

populated areas; however,

queer-identified individuals can also be

found living in both densely and

sparsely populated communities all

around the world.

Research on migration patterns between

urban and rural areas also challenges a

binary view of the two categories as

well as the common narrative that

queer-identifying individuals 'escape'

to the city over the course of their

lives. In Coming Out and Coming Back:

Rural Gay Migration and the City,

authors Meredith Redlin and Alexis Annes'

find that the migratory flow between

urban and rural is not unidirectional,

but rather a series of movements over

time between the two spaces. Their essay

illustrates how queer individuals move

within and between rural and urban areas

in response to the ways that each space

limits and/or enables their identity

formation and sexual expression.

Small Town in Ohio Has Its First Pride celebration and the

Community Loved it

Matt and Blue: Gay Family Living in a Small Town

Nature Doesn’t Care if You’re Gay or Straight: Meet the

Gay Farmers Queering Agriculture

Small Town Gay Pride Parade

F150 by Dixon Dallas

Orville Peck & Willie Nelson: Cowboys Are Frequently

Secretly Fond Of Each Other

The Aunties: Working Harriett Tubman's Farm

Not As Bad You You Think:

LGBTQ People in Rural America

How to Be Queer in Country Music: The

Story of Mya Byrne

Better This Way: Country Song by Doug Strahm

Wild West: Much Gayer Than You Think

Small Town in South Dakota: Champion for Its LGBTQ

Neighbors

Growing Up in a Small Town Made This

Couple Realize Not All Gay People Dream of Big City Life

Building a More LGBTQ Inclusive South

Pride Source: Real Gay Cowboys

Dancing in the Living Room: Country Song by Cameron Hawthorn

Rural Queer Lifestyle

In

rural areas, the heterosexual family

unit is valued as an essential part of

life. It is the overtly dominant

lifestyle in these spaces, which makes

being queer a different experience than

one would have in a metropolitan area.

Masculine and feminine gender

representations operate differently for

those in rural areas because work done

by both genders is perceived as

masculine behavior in other non-rural

areas. Both men and women can exhibit

masculine features and be perceived as

normal. Many rural women work alongside

men on farms or in construction work,

thus certain types of masculinity

displayed by rural women are not

interpreted as lesbian behavior as they

might be in an urban or suburban

environment. As a result of female

gender representations being more

masculine for women in rural spaces,

femininity operates very differently

there, and thus so does lesbianism. This

masculine dynamic allows for some

lesbians to blend in quite easily, where

typical female attire can be wearing

flannels and cowboy boots. However,

deviations in style, such as short hair

or wearing ties, can still result in

judgment from the woman's surrounding

community. Emily Kayzak notes that “the

sexual identity of rural butch lesbian

women is not invisible in urban lesbian

cultures, their more butch gender

presentations do not do the same work in

rural areas because those gender

presentations are also tied to normative

(hetero) sexuality.” Generally,

lesbian-butch women are compatible with

rural lifestyles as long as they can fit

in with the typical masculine-female

appearance. Rural spaces have even been

referred to as makings for “lesbian

lands,” in part due to their ability to

blend in.

In the 1970s, women began to move to

agricultural communes where they could

live and work with other “country

women”. In these communities, lesbian

women built communes where they grew

their own food and created societies

away from men. They believed that living

and working in nature allowed them to

embrace their inherent connection with

nature. Gay men also partook in similar

activities; Bell and Valentine note how

the Edward Carpenter Community in

England hosts Gay Men's Weeks where they

conduct events related to

free-spiritedness and the embracement of

one's sexuality.

Growing Up

Gay in Appalachia

Queer Survival in Mississippi and the Bars That Saved Us

TV Series: "Farming for Love" Features Gay Farmer Kirkland Douglas

Emmanuel the Emu and Farmer Taylor Blake

Drop by The Tonight Show

Finding

LGBTQ Community in the Rural South

Christopher Macken:

Growing Up Gay in the South

Info: LGBTQ Southern,

Grassroots, Local, Community Projects

Lesbian

Farmers: Redefining Rural America

I Lassoed Queer Joy in a Rodeo-Loving

Town

I'm Not in

Love With You by Justin Hiltner and Jon

Weisberger

Young Girl Growing Up Gay

in a Conservative Hometown

Clearly

Gay in Small Town Alabama

Unapologetically Southern and Queer:

Invisible Histories Project

DC Rawhides: Country Music Dancing

Fabulous

Chicken Coop

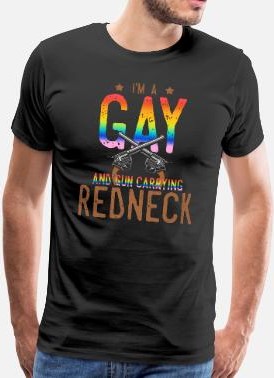

For rural men, on the other hand,

“publicly disrupting normative gender

expectations arguably remains as, if not

more, contentious than homoerotic

desires.” In many places, as long as a

gay man subscribes to masculine

representations and activities, such as

wearing traditionally masculine attire

and working in manual labor, acceptance

comes much more easily. Deviations in

appearance, like dressing up in drag,

would be seen as very unacceptable, and

can result in harassment. Male

effeminate expressions and rurality are

generally seen as incompatible. Many gay

men in rural communities reject

femininity and embrace masculine roles.

Feminine gays typically face persecution

and disapproval from their community

members.

Research on Rural LGBTQ

People of Color

Cameron Hawthorn: Oh Hot Damn!

Nature Doesn’t Care if You’re Gay or Straight: Meet the

Gay Farmers Queering Agriculture

PFLAG: Experiences of

LGBTQ Students in Small Rural Towns

In the Face of Discrimination: LGBTQ Farmers are Hopeful

Advocate: What is a

Cottagecore Lesbian?

Ride Me Cowboy by Paisley Fields

In Appalachia, Hell Hath No Fury Like a Trans Goth With a Banjo

Understanding Southern

Culture

Queer individuals in rural areas, as in

many other places, face discrimination

and violence. In small rural areas,

perpetrators and victims are typically

both known to the surrounding community.

Even police, who are intended to hold up

the law, are known to commit crimes

against sexually marginalized people.

Brett Beemyn's review of John Howard's

piece "Men Like That: A Southern Queer

History" explains some of the roots of

violent hate crimes and discrimination

against queer people. In the 1960s,

amongst the acrimony of racists was the

tendency to depict African Americans as

sexual deviants. In addition, during the

civil rights movement African Americans

were known to have queer allies, thus

stereotypes of racial justice supporters

as engagers in perverted sexual acts

became prevalent in the 1960s and the

focus of discrimination spread to

include queer individuals in a more

direct manner.

In contrast, queer urbanites have gained

much more acceptance and visibility as a

result of gay rights movements and the

recognition of the potential of the

queer economy. Acceptance of queerness

is also much more common in suburban and

urban communities, because there is a

higher acceptance of diversity in

general. All cities have recognized,

visible gay neighborhoods. Gay couples

are more likely to live in urban areas

than are lesbian couples, as the urban

setting can be much more conducive to

gay culture and life. Amongst those with

higher income or education, acceptance

is also more prevalent. These two points

have led to an increase of the migration

of queer people from rural communities

to metropolitan areas. The cost of

moving to a city filters out some with

lower incomes, creating a class bias for

those who are more affluent. Yet

discrimination from community members,

local police, and even state governments

still occurs in urban spheres, although

cities typically maintain a relative

liberalism.

Being LGBTQ in the Deep

South

Country Queers: Joy and Pain of Rural LGBTQ Life

Leslie Jordan: Southern Gay

The Aunties: Farmers Donna Dear and Paulette Greene

Continue Harriet Tubman’s Legacy

Matt and Blue: Gay Family Living in a Small Town

Building a More LGBTQ Inclusive South

Being LGBTQ in Rural

Spaces

Patrick Haggerty: Singer Who Recorded

First Gay Country Songs Dies at 78

Y'all Means All (Queer Eye): Miranda

Lambert

Small Town Gay Pride Parade

Better This Way: Country Song by Doug Strahm

Advocate: What is a

Cottagecore Lesbian?

Southern Queers: New

Study Reveals the Reality of LGBTQ

People in the South

Rural

Queer Farmers

Other

communities of queer farmers prefer to

live a more conventional lifestyle with

a house and agricultural land of their

own. The documentary Out Here

portrays the lives of many rural queer

people across the United States, and it

shows how many queer people make a

living and are making a difference in

their communities through agriculture.

The documentary's creators also provide

many biographies about queer farmers on

their blog. The farmers documented have

a wide variety of experiences, from

being a specialty cattle farmer to an

urban community gardener at a

non-profit. The farmers surveyed state

that they feel that farming provides a

place where it is free to experiment,

and is a place where queers naturally

belong. They also describe the

discrimination that they have faced

throughout their agricultural careers,

from social isolation to having

fungicide dropped on them in the field.

Farmers and Friends, a helpline for

closeted gay farmers in England, was

created to help farmers deal with

discrimination and to provide emotional

support. Many closeted queer farmers

risk being outed by their communities,

which could lead to loss of their

livelihoods and community ties.

The eco-queer movement aims to draw

attention to the intersectionality of

nature and sexuality. Part of this

intersectionality is the reason why many

queer individuals may not feel

comfortable in a rural setting due to

the population dynamics that generally

occur in these areas, which mainly

consist of straight, middle-class, white

men. Because of this, many queer farmers

have taken to growing food in urban

environments so that they can be

agricultural while maintaining their

queer lifestyles.

Same Old Country Love Song by Brian

Falduto

Atlanta: American South's Sweet Peach of

LGBTQ Progress

GLAAD Stories: LGBTQ Life

in the South

MAP Report: LGBTQ People

in Rural America

Being Queer in the Country

Christopher Macken: Growing Up Gay in

the South

Tyler Childers - In Your Love

Country Singer Chris Housman: Guilty as

Sin

Country Star Ty Herndon

Marries Boyfriend in Tennessee Wedding

Southern Queers: New Study Reveals the

Reality of LGBTQ People in the South

Small-Town Pride Celebrations Show LGBTQ

Life Is Flourishing in America

LGBTQ Youth in the South Face Greater Mental Health

Challenges

What Frank Ocean’s ‘Thinkin Bout You’

Meant To A Black Queer Boy In The South

Fabulous

Chicken Coop

Queer

Rural Political Activism

Many

queer political organizers believe

reform is more difficult to pass in

rural communities that are less tolerant

of queer lifestyles. It is harder to

mobilize communities in rural spaces

where queer populations are less dense

and financial contributions are limited.

This has led to a divestment in formal

rural queer political organizing.

Because political activism has been

silent in rural communities, many

Americans assume rural queer people do

not exist, or that they only do so only

before moving to more urban and

accepting communities. This assumption

has created a misrepresentation of the

US queer population. US Census data

shows that 66% of South Dakotan same-sex

households were located outside of urban

areas. Queer communities exist outside

urban areas, although they are generally

less visible.

A lack of visibility and political

attention has left queer people more

vulnerable to institutional

discrimination. Compared to the

heterosexual population, they have

reduced access to housing and healthcare

and face greater employment

discrimination. In South Dakota, only

29% of rural same-sex households own

homes, compared to 84% of married

heterosexual couples. There are

generally fewer community resources and

support groups for queer individuals in

rural areas, as more limited local

resources do not facilitate their

existence.

Gay Rodeo: Hall of Fame

LGBTQ Pride in Rural Missouri

Queer Survival in Mississippi and the

Bars That Saved Us

In Appalachia, Hell Hath No Fury Like a Trans Goth With

a Banjo

Photographer Luke Gilford Finds Queer Joy

in Queer Cowboys

Young Girl Growing Up Gay in a

Conservative Hometown

International Gay Rodeo Association: John King Interview

GLAAD Stories: LGBTQ Life

in the South

Info: LGBTQ Southern, Grassroots, Local, Community

Projects

Black and Gay in

Birmingham

Nature Doesn’t Care if You’re Gay or Straight: Meet the

Gay Farmers Queering Agriculture

Hometown:

Country Song

by Brandon Stansell

LGBTQ and Rurality

Understanding Southern Culture

Legislation often neglects rural queer

populations, leaving them without

protection under the law. In a 2006

custody case, a mother found herself

unfit to care for her child and

relinquished rights to a queer

caretaker. Once the new guardian's

sexuality was discovered the court ruled

against the biological mother's request,

stating that "the adoption would not be

in the best interest of the child." The

court used rurality in their reasoning

to reject the request, citing "stigma

that the child may face growing up in a

small, rural town with two women, in

whose case she was placed at the age of

six, who openly engage in a homosexual

relationship." The court found the state

of Georgia a more fit guardian than a

rural queer couple.

Despite similar cases, many fights in

rural areas are won in state courtrooms.

The Iowa Supreme Court struck down the

state's defense of marriage statute,

which made it one of the first states to

allow same-sex marriage, affecting the

predominantly rural population. This

action was met with political

resistance. The Iowa electorate voted to

not retain all three judges, marking the

first time in Iowa's history that a

judge had not been retained since 1961.

Many rural politicians have cited their

reluctance to come out in support of

same-sex marriage, for fear of similar

political repercussions. Representative

Paul Davis, the 2014 Democratic

gubernatorial nominee in Kansas, voted

against a constitutional ban on same-sex

marriage three times in the state

legislature, but did not take a

definitive stance on the issue in his

run for governor. More liberal and urban

districts can offer public officials a

politically safe place to take stances

on issues that are not popular in

predominantly rural states.

I Lassoed Queer Joy in a Rodeo-Loving Town

Advocate: What is a

Cottagecore Lesbian?

Orville Peck & Willie Nelson: Cowboys Are Frequently

Secretly Fond Of Each Other

Not As Bad You You Think:

LGBTQ People in Rural America

Point of Pride: How to Be

Queer in a Small Town

Finding LGBTQ Community in

the Rural South

TV Series: "Farming for Love" Features Gay Farmer

Kirkland Douglas

How to Be Queer in

Country Music: The Story of Mya Byrne

F150 by Dixon Dallas

In recent years, the country has seen a

shift in national public opinion on

queer issues, which has spread to rural

communities. In 2006, 71 Wisconsin

counties voted to ban same-sex marriage,

while only one county voted against the

ban. Opinion has since overwhelmingly

shifted. According to a 2014 poll by

Marquette Law School, only 35% of voters

in the Green Bay media market, a

predominantly conservative area, still

support the marriage ban, compared to

65% of the population in 2006.

Queer visibility plays a critical role

in political activism, though this has

not been a viable strategy for many

rural queer people. Being openly queer

can lead to more discrimination and

isolation in rural spaces. Rural queer

individuals have had to re-imagine how

to make political and social progress in

their communities. New digital media has

opened more political options for rural

queer people. Social media is a means to

expand local communities and allow rural

queer individuals to take part in a

larger queer community. Access to queer

people's experiences are available on

blogs and websites and provide access to

the terminology needed to describe and

understand their experiences. New media

can give rural queer individuals the

political tools and connections to make

changes in their own communities.

All American Boy: Country Song by Steve Grand

LGBTQ and Rurality

Advocate: LGBTQ People of

Color in Rural America

Emmanuel the Emu and Farmer Taylor Blake

Drop by The Tonight Show

Rednecks for Black Lives:

Southerners Fight for Racial Justice

Finding LGBTQ Community in

the Rural South

Country People: Gay Short

Film

Small-Town Pride Celebrations Show LGBTQ

Life Is Flourishing in America

LGBTQ Nation: Rural Pride Events

Ever Been to the Gay Rodeo?

Country Queers Project

When Rae

Garringer was growing up on a farm in

southeastern West Virginia in the 1980s

and 1990s, LGBTQ people (both real or

fictional) were nowhere to be found. “I

grew up without TV, and it was mostly

pre-internet, so I just didn’t know any

queer people,” Garringer, 35. “I never

met queer people my age, and I wasn’t

seeing queer representation in the place

that I existed; I just think I didn’t

even realize that it was kind of an

option.”

It wasn’t until Garringer, who uses

nonbinary they/them pronouns, moved away

to Massachusetts for college in 2003

that they met other LGBTQ people and

embraced their sexual orientation and

gender identity. After living away for

several years, first at university and

then in liberal Austin, Texas, Garringer

questioned whether they could live

openly and find a queer community of

friends back home. Then in 2011, after

eight years away, Garringer headed back

to the farm for a job opportunity and to

be closer to family.

Garringer,

who now lives in neighboring Kentucky,

said their move back to West Virginia

was “healing” and filled with “joy.” But

while queerness was not as hidden as it

had been, it was still far from easily

visible. “I was just really frustrated

that it was so hard to find rural queer

stories and histories, and it was also

very hard to find each other in

small-town spaces,” Garringer said.

So in 2013, feeling a need to find a

sense of community, Garringer had an

idea. They carried a tape recorder and

set out to document the diverse

experiences of LGBTQ individuals living

in rural towns across the United States.

Those interviews turned into Country

Queers, a multimedia, oral-history

project. The stories collected by

Garringer over the years have been

shared on the Country Queers website and

Instagram page, and starting June 30,

the new Country Queers podcast

will debut on Apple Podcasts, Spotify

and Stitcher.

Angel Olsen: All The Good Times

Christopher Macken: Growing Up Gay in the South

Over Half of LGBTQ

Southerners Say Parents Tried to Repress Their Identity

Country Singer Chris Housman: Guilty as Sin

LGBTQ Pride Celebrations Held in Rural or

Small-Town America

Pride Source: Rural Americans Are LGBTQ Too

Being LGBTQ in the Deep

South

Country Queers: Joy and Pain of Rural LGBTQ Life

Leslie Jordan: Southern Gay

For the

past seven years, Garringer has

interviewed 65 people from 15 states

(from Arizona to Vermont )and has

collaborated with queer organizations

including the Two Spirit National

Cultural Exchange, the Kansas Queer

Youth Network and the International Gay

Rodeo Association. With the help of a

Kickstarter campaign, Garringer was able

to buy a camera and take a long road

trip to six states in the summer of

2014, driving a total of 7,000 miles to

interview 30 people in 30 days. In a

piece Garringer wrote for Scalawag,

a Southern storytelling website, they

said their aim is to share stories that

portray “the full contradictory glory

that is human life. I believe in the

power of those of us living an

experience daily sharing stories of the

messy complicated joy, pain, monotony

and fabulosity of rural and small town

queer life."

Early on in the project, it was clear to

Garringer that rural queer experiences

are not monolithic, which is why

Country Queers aims to document

rural, queer people of different races,

ages, religions, socioeconomic

backgrounds and occupations.

[Source: Gabriela Martinez, NBC News,

June 2020]

Country Queers:

Podcast

Country Queers: Joy and Pain of Rural LGBTQ Life

Gay Rodeo: Hall of Fame

Southern Queers: New Study Reveals the

Reality of LGBTQ People in the South

Building a More LGBTQ Inclusive South

Growing Up Gay in

Appalachia

Photographer Luke Gilford Finds Queer Joy

in Queer Cowboys

LGBTQ Pride in Rural Missouri

International Gay Rodeo Association: John King Interview

Conversation with Gay Fly

Fisherman

Hometown:

Country Song

by Brandon Stansell

Growing Up in a Small Town Made This

Couple Realize Not All Gay People Dream of Big City Life

GLAAD Stories: LGBTQ Life

in the South

Not As Bad You You Think:

LGBTQ People in Rural America

Queer in Rural America

Being Gay in Tennessee

Wasn't Always Easy

LGBTQ and Rurality

LGBTQ People: Fundamental

Part of the Fabric of Rural Communities

Patrick Haggerty: Singer Who Recorded

First Gay Country Songs Dies at 78

Growing Up Gay in a Small

Conservative Texas Town

Research on Rural LGBTQ

People of Color

Queering the Redneck

Riviera

Advocate: What is a

Cottagecore Lesbian?

Josh Burford: Chronicler of Southern LGBTQ History

Clearly Gay in Small Town

Alabama

TED Talk: The LGBTQ

Community Could Save Small Towns

MAP Report: LGBTQ People

in Rural America

Wild West: Much Gayer Than You Think

Invisible Histories

Project: Gay Southern History

Lesbian Farmers:

Redefining Rural America